What is most important in the world? There is surprising consensus about what it is not!

We have heard light-hearted comments like: “You can’t take it with you.” We have heard the modest words of an older person: “At least I have my health.” Or words to the effect: “No one has engraved on their headstone, “I should have spent more time in the office.”” Shakespeare, in Othello (Act III, Scene 3), wrote these timeless words about damage to reputation:

Good name in man and woman, dear my lord,

Is the immediate jewel of their souls.

Who steals my purse steals trash.

‘Tis something, nothing:

‘Twas mine, ’tis his, and has been slave to thousands.

But he that filches from me my good name

Robs me of that which not enriches him

And makes me poor indeed.

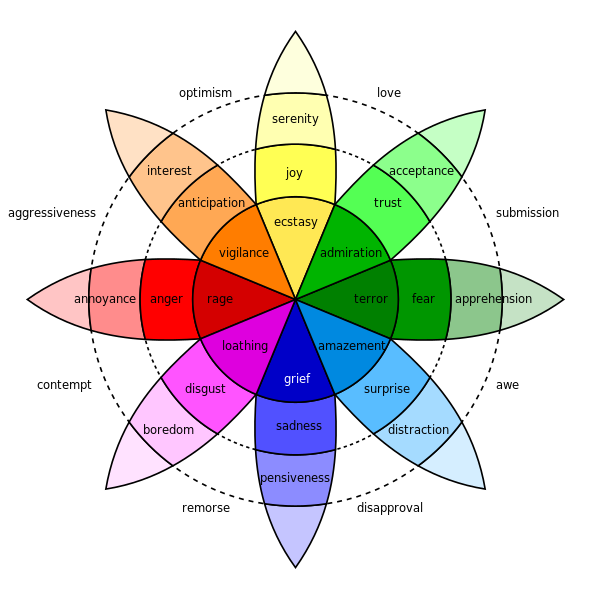

Taken together, we all agree that the most important things in life are not purely monetary. Patrick Henry proclaimed: “Give me Liberty – or give me death!” Many brave men and women have given their lives for others – for freedom! There are things greater than ourselves that are worth more than life itself. Things like health, reputation, time with loved ones, family, friendship, a kind word from a mentor, teacher, parent, co-worker, sibling, child, time with a beloved pet or companion animal, a sense of achievement or accomplishment, service to the public, service to others, productive labor, peace of mind, peace, freedom, justice, for example, are priceless. We all know this to be true. Yet when it comes time to put dollar values on such priceless things, we all can get confused and stymied. How do we put a price on the priceless?

One thing jurors agree on is this: “Just because something is priceless, does not mean it is worthless!” How do we lend dignity to the loss of priceless things? This is not just a rhetorical question. We ask juries across the country to value the loss of such things every day.

I have spoken to many jurors during the process of jury selection known as voir dire* and explored this very question. I have asked if jurors had ever had a beloved pet. Could the value of this pet be calculated based on purchase price, vet bills, costs of food? Is a pet is rescued from the pound worth less than a show breed in terms of our feelings of loss? Clearly the “economic” value of a pet is different that the “noneconomic” value of a pet. If someone takes a beloved pet from you or your child, does it fully compensate for that loss to pay, say, the purchase price? What about pain or injury you or someone else sustains as a result of someone’s carelessness or negligence? If an injury costs you a hand, a leg, an eye, your peace of mind, is it enough to pay you the cost of medical bills and call it even?

The law says that the jury should compensate for both special (specific) damages and general damages, which correspond to economic and noneconomic damages. Special (economic) damages are all the kinds of losses that have a price tag: medical bills, damage to property, lost wages, loss of future work or business opportunities, breach of contract, failure to pay money owed, financial losses. General (noneconomic) damages are all those things that do not have a price tag: pain, suffering, disability, damage to the marital relationship, damage to the parent-child relationship, emotional distress, humiliation, damage to reputation, loss of peace of mind and enjoyment of life.

Washington law, in RCW 4.56.250(1), defines economic and noneconomic damages in actions for personal injury or death. Economic damages are “objectively verifiable monetary losses, including medical expenses, loss of earnings, burial costs, loss of use of property, cost of replacement or repair, cost of obtaining substitute domestic services, loss of employment, and loss of business or employment opportunities.” RCW 4.56.250(1)(a). Noneconomic damages are “subjective, nonmonetary losses, including, but not limited to pain, suffering, inconvenience, mental anguish, disability or disfigurement incurred by the injured party, emotional distress, loss of society and companionship, loss of consortium, injury to reputation and humiliation, and destruction of the parent-child relationship.” RCW 4.56.250(1)(b).

In Washington State, juries are provided with the Washington Pattern Instructions (WPI) through which the Court provides jurors with instructions as to the applicable law. WPI 30.01.01[Measure of Economic and Noneconomic Damages—Personal Injury—No Contributory Negligence] states in pertinent part:

It is the duty of the court to instruct you as to the measure of damages. [By instructing you on damages the court does not mean to suggest for which party your verdict should be rendered.

If your verdict is for the plaintiff, then] you must determine the amount of money that will reasonably and fairly compensate the plaintiff for such damages as you find were proximately caused by the negligence of the defendant.

* * *

The burden of proving damages rests upon the plaintiff. It is for you to determine, based upon the evidence, whether any particular element has been proved by a preponderance of the evidence.

Your award must be based upon evidence and not upon speculation, guess, or conjecture.

The law has not furnished us with any fixed standards by which to measure noneconomic damages. With reference to these matters you must be governed by your own judgment, by the evidence in the case, and by these instructions.

[Emphasis added.]

Although the 1986 Tort Reform Act originally capped the amount of noneconomic damages that may be recovered pursuant to a formula based on a percentage of the average annual wage and the life expectancy of the person incurring the damages, this cap was later struck down as unconstitutional in Sofie v. Fibreboard Corp., 112 Wn.2d 636, 771 P.2d 711, 780 P.2d 260 (1989) (interpreting the constitutional right to a jury trial). So, we know one thing for sure, the Legislature is not going to be able to give the jury a “formula.” Assessing and valuing this special kind of loss is uniquely within the province of the jury. Although it is difficult, it is a job that can – and must – be done.

One answer that is NOT the right answer is the idea that no amount being sufficient to compensate for noneconomic loss, justifies awarding nothing at all. After all, in a wrongful death case, one can always say: “Money won’t bring him/her back.” So, why award anything at all? The answer is in the title of this blog: something being priceless is not worthless; we must lend dignity to the loss. If no amount is enough, it does not follow that awarding nothing is enough.

Why is nothing not enough? One key reason is that tort law, which protects all of us from wrongful conduct, would be undermined by failing to award damages. Tort law (as opposed to criminal law) provides remedies for civil wrongs that injure others (other than those arising out of contractual obligations) including claims for personal injuries or wrongful death arising from negligence, defamation, trespass, invasion of privacy, infliction of emotional distress, and fraud, to name a few. Tort law provides essential protections for our individual rights in two ways: first, it seeks to compensate victims of past wrongs; second, it seeks to deter careless, injury-producing behavior in the future. Through compensation to the victim, the innocent are given means to move on; at the same time, such remuneration also vindicates legal rights and interests and affirms their value in the society at large. By shifting the costs of injury to the person legally responsible for inflicting them, it punishes wrongdoing, both deterring a repetition of the harmful act and providing incentives for improved behavior. Failing to award damages for noneconomic losses means that innocent victims are not fully compensated and that guilty wrongdoers are insufficiently deterred.

A jury is required to award damages for every element of loss. If a person has medical bills that are awarded, it has been held to be error not to award anything for pain and suffering that necessarily accompanied the injury. On relatively rare occasions where a jury has failed to award any noneconomic damages, the court has invoked its power of additur adding to the verdict damage amounts in addition to those awarded by the jury.

Lacking fixed standards, jurors must use their own personal experience and judgment to award noneconomic damages. How may this be done? In my next blog, I will suggest some approaches that may help. So, stay tuned for Part II.

* For those who are interested, voir dire is derived the Norman French; it was William the Conqueror who brought the jury system to England from Normandy during the “Norman Invasion” in 1066. It does not mean, as it might in modern French, “voir” (“to see”) “dire” (“to say”), but comes from the Latin word verum, meaning truth and dictum meaning speech and so is properly translated as “truthful speech.” The same roots lives on in such words as verity, verify, dictate and dictionary. During the voir dire (jury selection) process at the beginning of a case, jurors are sworn to speak truthfully about their qualification to serve. The word “verdict” at the end of trial, completes the neat set of bookends at the beginning and end of a case, since it also means “truthful speech.” In voir dire, the jurors are speaking truthfully about their own fitness to serve; in the final verdict, the jury is speaking truthfully as to the justice of the case.